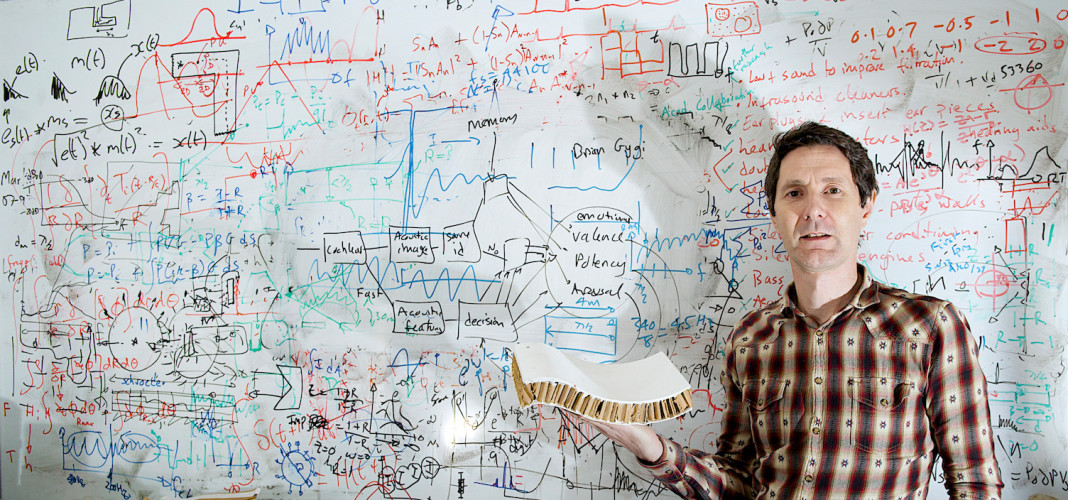

Trevor Cox is the professor of Acoustic Engineering at the Salford University. In his amazing book Sonic Wonderland, A Scientific Odyssey of Sound, the sound is the main actor on the stage and we can follow it through the voice of Cox who says: “a compelling tour of the world’s most amazing acoustic phenomena and a passionate plea for a deeper appreciation of and respect for our shared sonic landscapes”.

A scientific book about sound finally written in a simple and clear language able to amplify the common interest about this theme, where prof. Cox invites us not to be passive listeners but to open our ears and our mind to the majestic cacophony that surrounds us.

In this interview, Cox talks with us about his point of view on old and new techniques of buildings concerning acoustic effects or the use of reverberation in some specific places or again the change in global soundscape over the centuries.

At the beginning of your book, you talk about acoustic problems related to indoor environments such as schools, illustrated by the example of the Business Academy Bexley. How much are more architecture and sound far apart in the planning stages?

Trevor Cox: Most architects receive little training in sound, and so are reliant on advice from an acoustic consultant. For this reason, a good relationship between architect and acoustician is vital. A big change in design methods is happening now, where acoustic engineers play architects examples of how their building will sound. This is transforming the acoustic design of buildings because listening to examples allows architects to make better informed decisions.

About the use of reverberation, you quote many examples ranging from classical music to Brian Eno and the evocative experience of the most reverberant site in the world but I was particularly impressed by your considerations about the acoustic of prehistoric sites such as the burial chambers. How important it is for contemporary man rediscover how our ancestors were listening?

TC: Visitors to prehistoric site such as a burial chamber or stone circle should think about how places sounded to our ancestors if they want to better understand these precious sites. Rituals would have taken place in or around these places, and nearly all human rituals involve sound. The acoustic, whether good or bad, would have influenced how these places were used.

Animals show a variety of ways and an amazing adaptive ability, you describe numerous examples such as real dialects in the case of birds. Men, unlike animals, also seem to need an evocative component in relation to sound, what do you think? How we evaluate the sounds based on what they remember us and not according to what they are from an acoustic point of view?

TC: For much of what we hear, our reaction is first determined by what we think is causing the sound. If you hear a car, you don’t think vroom, you think car. Then our reactions to the sound have a lot to do with how we react to the car. Of course, cars make different sounds, so a sports car might have a particular bass throb conveying a sense of power. In this case, some of our response are about the character of the noise rather than what is making it. Bass sounds are generally associated with larger, more powerful things.

The change in the global soundscape over the centuries is evident, in the ninth chapter of your book you deals with the topic by mentioning the introduction of the typical sounds of the industrial age. Do you consider as positive this soundscape’s evolution?

TC: It is hard to think positively about industrial noise as this can be responsible for noiseÂinduced hearing loss or aircraft noise that causes sleep deprivation and harms attainment by pupils in schools. But this is the soundscape of progress that has lead to longer and healthier lives. What we need to get better at is at managing the noise so it causes less problems.

In a very beautiful excerpt of your book, you talk about the need to pass on to posterity an auditory documentation of the places that means preserving the soundmarks so to not lose the tracks of sound pictures of places that otherwise would be forgotten. What can we do to stimulate the sensibility on this argument?

Fortunately, this preservation is beginning to happen almost by chance. We’re now carrying out mobile phones that record video with soundtracks. So many special sounds are being captured.

About musical productions of last years, do you think is there a trend in the use of sound?

The biggest change in music productions in my lifetime is the shift from analogue to digital that contributed to overly loud music that lacked dynamics. There are some hopeful signs that this loudness war may be over and we can return to better-produced music.

If anyone would like to know more about the world of sounds, what kind of readings or albums do you recommend?

I would recommend just listening. Nothing special is needed, just spend some of the day listening to what is around you. The Soundscape by R. Murray Schafer is the seminal book on listening and acoustic ecology. Or you could go back to old authors like Thomas Hardy who had a beautiful way of writing about sound. In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise by George Prochnik is the best of the recent books on silence.

If you want to know more about Trevor Cox you can visit his blog, the SoundCloud account or the project called Sound Tourism.

[Featured image by Flickr user]